Transient, Fleeting: The World of Ishimoto Yasuhiro part 17

Individual Realism

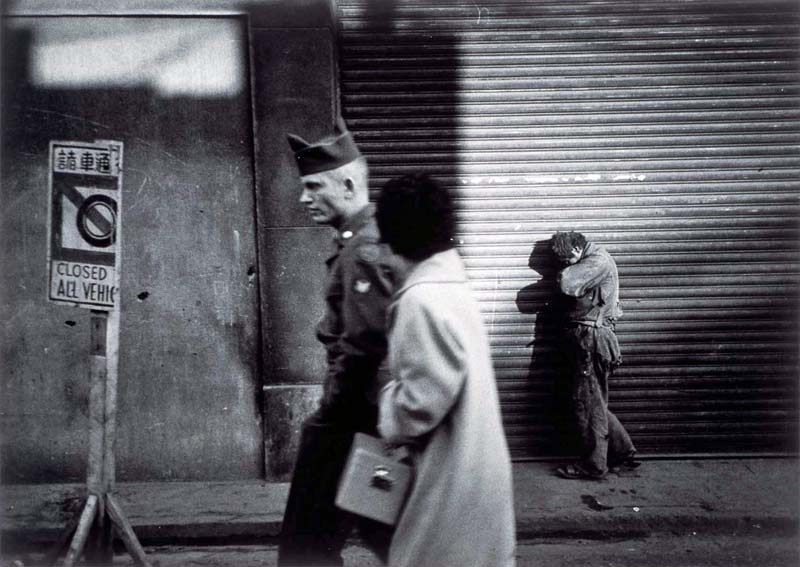

“This is in front of Wako in Ginza. Just when I was about to shoot the vagrant kind of man in the back, a soldier of the Allied Occupation forces and a prostitute passed by, so I released the shutter in that moment. It was in the winter, at 4 or 5 in the afternoon I think.” 50 years ago, there was no sign of the pomp and glory that the Ginza district is known for today.

Many of the people in Ishimoto’s photographs display human dignity regardless of their low social standing and poverty, and radiate the energy of being alive in all their quietness, while only few of his works are entirely filled with a feeling of emptiness like this one here.

At a Ginza street corner, a soldier and a prostitute are about to disappear into the darkness of the night, while behind them a vagrant turns away as if trying to erase his existence altogether. The scenery might have looked less desolate if the woman was looking straight ahead, but she is in fact turning around and looking at the man. It is the gentle evening light enshrouding the vagrant that defines silhouettes like hers. This picture contains two fictitious couples. As suggested also by the letters “CLOSED” on the old street sign, everything seems to be closed here, and I can’t help but feel that this is how Ishimoto must have felt upon returning to postwar Japan for the first time in 14 years.

After Japan’s defeat in the war in 1945, the occupation troops under General MacArthur were distributed across the country. In ’52, the San Francisco Peace Treaty took effect, and the GHQ and occupation by the US Forces came to an end. In the following year, Ishimoto finished his schoolwork and returned to Japan.

It was exactly the time when the realist style was blooming in Japanese photography. LIFE and other pictorial magazines and photo books were imported from Europe and America, so people in Japan got more and more opportunities to see what was going on in photography on an international level. Against this backdrop, I think Ishimoto’s return was for Japanese photography like a gift from heaven, but as a matter of fact, all he got in response was a cold shoulder.

What he was apparently focusing on first and foremost were the realms of art, design and architecture. Together with the likes of Kenzo Tange, Sori Yanagi, Yusaku Kamekura and Taro Okamoto, Ishimoto was involved in the establishment of the International Design Committee of Japan (today the Japan Design Committee), and with support from up-and-coming artists and educators, he was offered a position as a teacher at Kuwasawa Design School, the first design school in Japan that opened in 1954.

It obviously took a while for the realm of Japanese photography to mature and finally assimilate the rigid formative art that Ishimoto displayed in his photographic work. ”I am more than a little dissatisfied with the “news photography first” – if not “news photography only” – attitude of Japanese photographers. The art of photography isn’t supposed to be that narrow-minded.” (Geijutsu Shincho, 1954)

The realist style that became popular especially among amateur photographers gradually developed the importunateness to fasten its teeth on the disadvantaged, which prompted some critics to describe the style cynically as “beggars’ photography”. What Ishimoto has probably shown to those people must have been his own style of realist photography that, like this picture here, does not snuggle up to misfortune.

(Published on August 1, 2006)

Kageyama Chinatsu, curator at the Museum of Art, Kochi

Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center