Transient, Fleeting: The World of Ishimoto Yasuhiro part 3

The New Bauhaus

The Chicago Institute of Design (aka New Bauhaus) was established in Chicago in 1937. The faculty consisted of a number of leading figures in the realms of modern architecture and photography, such as photographers Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind, as well as architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Buckminster Fuller, creator of the Fuller Dome.

Ishimoto studied here from 1948 until 1952. In addition to the Photography department, the New Bauhaus had Design, Architecture and Industrial Design departments. After going through the same curriculum for two years, students were separated into specialized classes in the third year.

The curriculum began with “scribbling”. Students weren’t given particular themes, and not even instructions regarding drawing methods from their teachers. As everyone sooner or later got tired of doing the same scribbling day in, day out, students naturally began to experiment by changing the way they held their pencils, or using different kinds of paper or tools. By doing so, they ultimately learned how using different materials resulted in different drawings.

In other classes, students worked with wood or metal to create ”hand sculptures” that “felt good” in their hands, whereas the creative process began with making the tools first. Here students acquired the ability to grasp through their sense of vision alone the relationship between materials and tools, the volume of a body, and the texture of a material that is normally understood through touch. By tackling such assignments as “join together different materials like metal and glass,” they worked out the simplest possible ways of joining materials by themselves, which sometimes resulted in totally new joining techniques. Through their work on such tasks, the students developed something like a cutaneous sense for materials (objects), and the ability to be creative without being restricted by manuals.

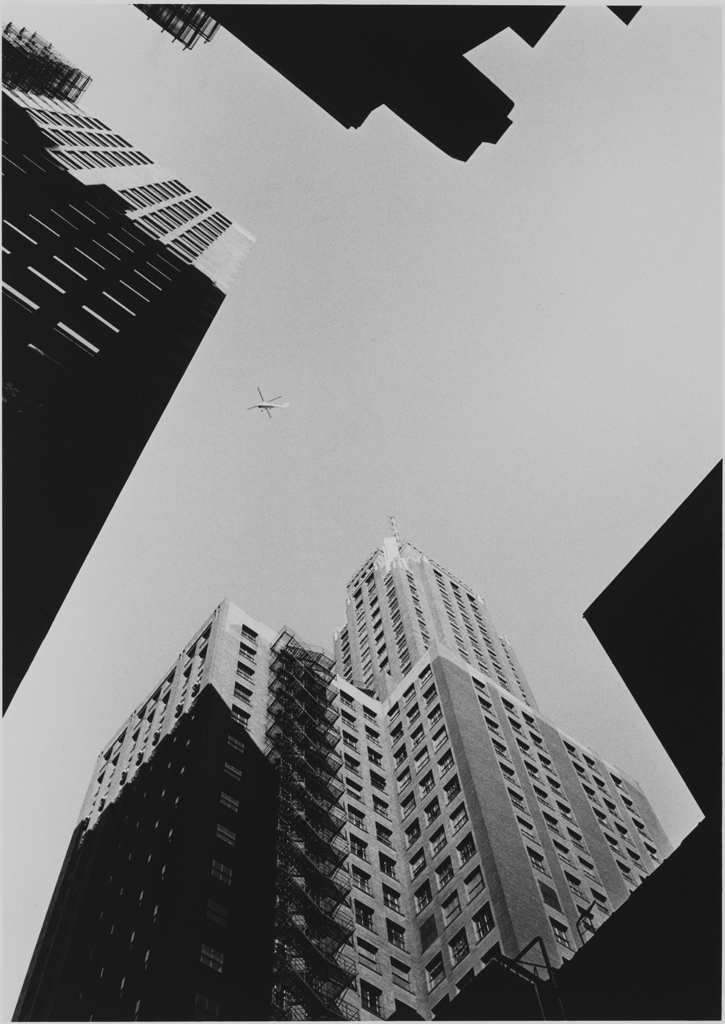

Likewise, students in the photography classes weren’t taught concrete techniques. One assignment was to “take photos 90% of which are occupied by the sky.” Again, there was no further specification. Without really comprehending the task, each student went out and started shooting pictures of the sky. Ishimoto was one of them. It was through developing these photographs that he realized a number of things for the first time. There were several pinholes caused by dust in the camera on the original sheets, and the prints clearly showed development irregularities and fingerprints.

The pinholes were caused by dust that had piled up inside the accordion-like body of the camera, and that came falling down as soon as the camera was pointed upward, and even the slightest fingerprint and irregularity was clearly visibly due to the fact that large parts of the prints were showing the (white) sky.

The profession of a photographer is to capture moments. Those opportunities must not be missed, as they won’t come again. “Always keep you camera in order so you’re prepared to shoot under the best possible conditions at any time!” Furthermore, “take meticulous care when developing and printing to make the best of each shot.” Taking “photos 90% of which are occupied by the sky” taught the students the things that a photographer should definitely do in order to produce good works. Ishimoto became aware of such things for himself, while other students must have made their own discoveries as well.

The teachers at this school carefully worked out such assignments through which students learn to think and understand meanings by themselves, and which they would fling at the students in just a few words. After that it’s the student’s turn to tackle the assignment until the penny drops, without ever being interrupted by the teacher. Those were the classes that nurtured the photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto.

(Published on June 7, 2005)

Kageyama Chinatsu, curator at the Museum of Art, Kochi

Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center